[CHRB] Rule Without Law: Prolonged Pre-Trial Detentions of Human Rights Defenders (1/23-29, 2015)

Comments Off on [CHRB] Rule Without Law: Prolonged Pre-Trial Detentions of Human Rights Defenders (1/23-29, 2015)![[CHRB] Rule Without Law: Prolonged Pre-Trial Detentions of Human Rights Defenders (1/23-29, 2015)](https://www.nchrd.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Beijing-police-released-Transition-Institute’s-managing-director-Huang-Kaiping-黄凯平-on-January-28-following-110-days-of-enforced-disappearance-504x380.jpg)

China Human Rights Briefing

January 23-29, 2015

Contents

Arbitrary Detention

- Rule Without Law: Prolonged Pre-Trial Detentions of Human Rights Defenders

Enforced Disappearance

- After Enforced Disappearance of 110 days, An Activist Is Released

Arbitrary Detention

Rule Without Law: Prolonged Pre-Trial Detentions of Human Rights Defenders

During a string of crackdowns since the spring of 2013, CHRD has documented an alarming number of excessive pre-trial detentions of human rights defenders (HRDs), who were not brought in front of a judge after having been in police custody for at least eight months, and with some held for more than a year-and-a-half. Such prolonged detentions violate Chinese law, and they have seemingly increased even as President Xi Jinping, who came into office in March 2013, has touted a principle to “rule the country with law.”

Among HRDs detained and then formally arrested in the crackdown on free assembly, association, and expression in 2013 and during suppression around the 25th anniversary of the Tiananmen Massacre in May and June 2014, the following individuals have been in police custody for at least eight months without being brought before a judge (detention lengths are indicated):

- For over 20 months: Huang Wenxun (黄文勋), Yuan Fengchu (袁奉初, aka Yuan Bing 袁兵), and Yuan Xiaohua (袁小华) in Chibi City, Hubei Province;

- For nearly nine months: Pu Zhiqiang (浦志强) and Qu Zhenhong (屈振红) in Beijing; Tang Jingling (唐荆陵), Wang Qingying (王清营), and Yuan Xinting (袁新亭) in Guangzhou; and Jiang Lijun (姜力均) and Sun Haiyang (孙海样) in Liaoning Province; Sheng Guan (圣观, real name Xu Zhiqiang 徐志强) and Huang Jingyi (黄静怡, real name Huang Fangmei, 黄芳梅) in Wuhan City, Hubei Province; and Jia Lingmin (贾灵敏), Dong Guangping (董广平), Hou Shuai (侯帅), and Yu Shiwen (于世文) in Zhengzhou City, Henan Province;

These individuals should never have been detained in the first place for exercising their rights to freedom of expression, assembly, or association, and for doing human rights or legal work, and they should be released immediately. In these cases, police and prosecutors have seemingly worked in concert to exploit loopholes in China’s Criminal Procedure Law (CPL) for political ends. Many of these HRDs have been held under incommunicado detention and denied lawyer visits. In addition, CHRD has documented that some have been tortured, including by being beaten, denied adequate medical treatment, or forced to do hard labor.

Apparently treating the cases against prominent HRDs as involving “major crimes,” authorities have arbitrarily applied provisions in the CPL, which should actually be applicable in rare, exceptional cases, to deprive them of due process rights. Among the violations is of their right “to trial within a reasonable time or to release,” as stipulated under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (Article 9). China has not ratified this Covenant but, as a signatory, is obligated not to violate it.

The CPL permits criminal detention for 37 days before arrest or release (Article 89). Following a formal arrest, a detainee can face periods of investigation of over one year, as a case is built against them. The CPL gives police between three to 10 months (Articles 154, 156-8) before recommending indictment, but the lengthy period of pre-trial detention is applicable only to cases involving “major crimes” or when the suspect has “committed a new crime,” subject to procuratorate review. After a recommendation for indictment, a procuratorate can send a case back to police twice for more investigation, giving authorities a further six-and-a-half month period before deciding to prosecute (Articles 169, 171).

Police have recommended indictments in many of the above cases, only to have a procuratorate send them back for further investigation, repeatedly in some cases, indicating that a criminal case may be weak. Following an indictment, the CPL states a court must announce a verdict on a case within three to six months, but this has been grossly violated in some cases.

Enforced Disappearance

After Enforced Disappearance of 110 days, An Activist Is Released

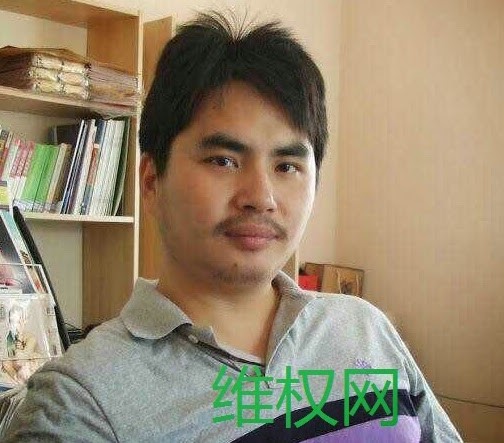

Beijing police released Transition Institute’s managing director Huang Kaiping (黄凯平) on January 28 following 110 days of enforced disappearance (image: RDN)

Huang Kaiping (黄凯平), the managing director of the Beijing-based independent think tank Transition Institute, returned home on January 28 after being disappeared for 110 days. Huang still does not know where he was held, according to a lawyer who spoke with him. Huang said that he could not answer any questions about torture, but said his captors blindfolded him and that he needs to get a medical examination to assess his health. After Beijing police took Huang away from his office on October 10, his family never received legal documentation nor could find out from authorities regarding his whereabouts and the reason for detention. Police reportedly accused Huang of “creating a disturbance,” which is ostensibly tied to his support for the pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong last fall, though his detention is likely also connected to a wider crackdown on NGOs. Two of Huang’s colleagues are still detained at Beijing No. 1 Detention Center, both charged with “illegal business activity.” Guo Yushan (郭玉闪), the group’s founding director, was formally arrested on January 3. Authorities have reportedly approved the arrest of He Zhengjun (何正军), the Transition Institute’s administrative director. Another detainee, writer Kou Yanding (寇延丁), who is affiliated with Transition, has been held under criminal detention on suspicion of “creating a disturbance” since October. She is also being held at Beijing No. 1 Detention Center.[1]

It is conceivable that Huang is a victim of Article 73 of the Criminal Procedure Law, which allows for individuals to be placed under “residential surveillance” at a “designated location” for up to six months for cases involving suspicion of endangering state security, terrorism, and major bribery, and when serving residential surveillance at home would be deemed by police to “hinder the investigation.” While the provision stipulates that families must be notified of residential surveillance within 24 hours, it does not indicate that they must be told the place of detention. In practice, this provision sanctions state enforced disappearance, which is prohibited by the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance. China has not signed this Convention.

Contacts:

Renee Xia, International Director (Mandarin, English), +1 240 374 8937, reneexia@chrdnet.com, Follow on Twitter: @ReneeXiaCHRD

Victor Clemens, Research Coordinator (English), +1 209 643 0539, victorclemens@chrdnet.com, Follow on Twitter: @VictorClemens

Frances Eve, Research Assistant (English), +852 6695 4083, franceseve@chrdnet.com, Follow on Twitter: @FrancesEveCHRD

Follow CHRD on Twitter: @CHRDnet

[1] “Huang Kaiping, Transition Institute Manager, Returns Home After Enforced Disappearance”(遭强迫失踪的传知行执行所长黄凯平今获释回家), January 28, 2015, RDN.