Individuals Affected by Crackdown on Civil Society Following Call for “Jasmine Revolution”

Comments Off on Individuals Affected by Crackdown on Civil Society Following Call for “Jasmine Revolution”

Last update: August 1, 2014 (this page is no longer being updated)

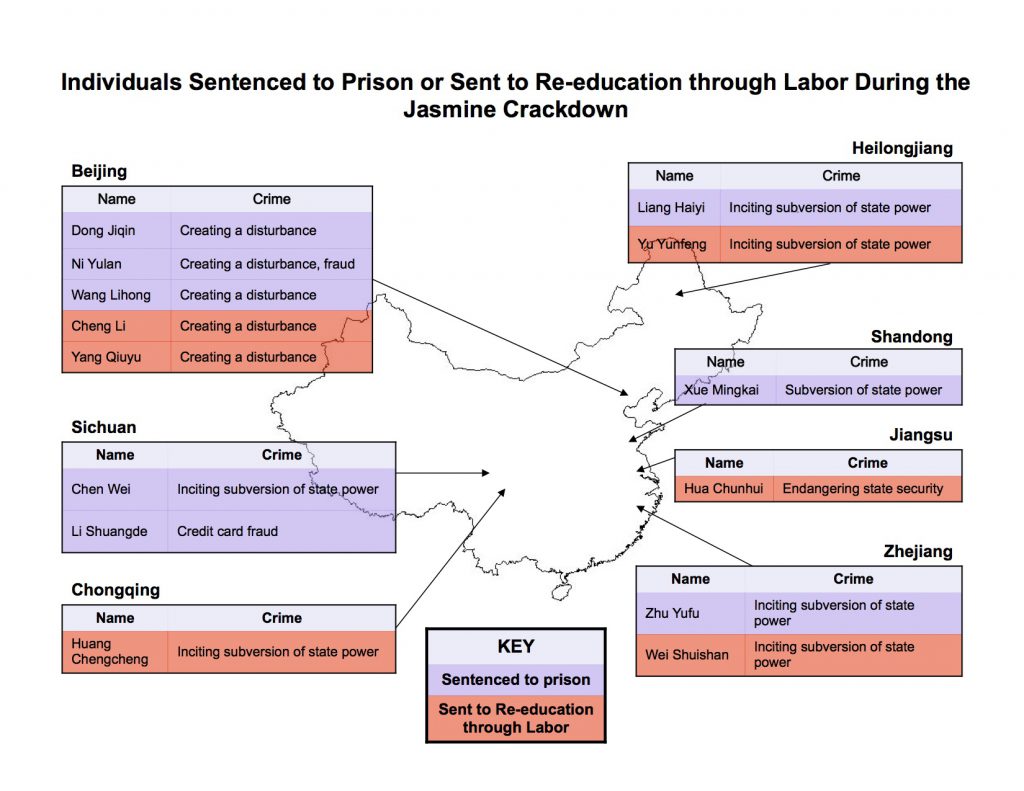

CHRD documented case of 82 individuals who the Chinese government detained or disappeared beginning in mid-February 2011 in a crackdown on civil society after online calls for “Jasmine Revolution” rallies first spread in China. Of these, 51 were put under criminal detention, including 11 known to have been formally arrested. Of those, eight were known to have been convicted of crimes and issued prison sentences, and three were placed under “residential surveillance.” Also, five individuals were sent to Re-education through Labor (RTL) camps, and 35 were released after other detentions or punishments. In addition to those who were criminally detained, two individuals were known to have been held in psychiatric hospitals, and four others were placed under illegal residential surveillance outside of their homes. CHRD also verified that at least 25 individuals were subjected to enforced disappearance during the crackdown.

The following map displays the names and charges against those known to have been sentenced to prison or sent to RTL (click on map to enlarge). Please see below for more detailed accounts of known arrests, detentions, and disappearances.

Formal Arrests

(Those in bold are currently detained)

- Chen Wei (陈卫), a rights activist based in Suining City, Sichuan Province, was formally arrested for “inciting subversion of state power” on March 28, 2011. Chen was criminally detained for “incitement” on February 20 after police in Suining called him for “tea” that same morning. Officers and security guards later searched his home, confiscating a computer, two hard drives, and a USB drive. On December 23, 2011, Chen was convicted of “incitement” and sentenced to nine years in prison. Prior to the 2.5-hour-long trial, Chen’s lawyer had encountered constant obstructions in meeting with his client; they met only twice–in September and November–in blatant violation of China’s Lawyers Law. Serving his current sentence at Jialing Prison in Nanchong City, Chen was a 1989 Tiananmen student protester from the Beijing Institute of Technology, majoring in mechanical engineering. He was imprisoned in Qincheng Prison and released in January 1991. In May 1992, Chen was again arrested for commemorating June 4 and organizing a political party, and was sentenced to five years in prison. In the past several years, Chen has emerged as a leader in organizing human rights actions in Sichuan.

- Ding Mao (丁矛), a dissident from Sichuan Province, was seized from his home on February 19, 2011, and criminally detained the next day by police in Mianyang City on suspicion of “inciting subversion of state power.” His case was transferred for a second time to the procuratorate in August. On December 1, Ding was released from the Mianyang City Detention Center and placed under six-month residential surveillance. CHRD learned of his arrest on March 28, 2011, and then was informed on April 9 that police in Mianyang City have blocked meetings between Ding and a lawyer hired for him by his family because, according to the police, Ding’s case “involves state secrets.” As a philosophy student at Lanzhou University in the late 1980s, Ding became a student leader during the 1989 pro-democracy protests. He was twice imprisoned for his activism, first in 1989 and again in 1992 when he was arrested for organizing the Social Democratic Party. He spent a total of 10 years in jail. Before his February detention, he was the general manager of an investment company in Mianyang.

- Dong Jiqin (董继勤), husband of housing rights activist and human rights lawyer Ni Yulan (see below), was detained in April of 2011 and formally arrested in May along with his wife and on the same charge–“creating a disturbance,” for hanging a banner outside the Yuxinyuan Guest House, his residence at the time. Dong and Ni disappeared in early April, and family members only discovered their whereabouts on April 11 after contacting the police. On July 13, 2011, Dong’s case was transferred to the procuratorate for review, and sent back to public security on August 2 for further investigation. Dong and Ni had their case heard by the Xicheng District People’s Court on December 29, 2011, but no verdict was announced. On April 10, 2012, the court announced that Dong was guilty of “creating a disturbance” and sentenced him to two years in prison. He was held in the Xicheng District Detention Center in Beijing’s Haidian District and released on October 5, 2013. Dong reportedly struggled with his health in detention, according to his daughter, who also said that she did not receive several letters that he wrote to her.

- Gao Chunlian (高纯炼), an elementary school teacher, rights activist, and Charter O8 signatory from Xianning City, Hubei Province, was taken into criminal custody on February 28, 2011, one day after a “Jasmine Stroll” protest in Wuhan and right after he posted an article online. He was formally arrested for “inciting subversion of state power,” according to his family, which received an arrest notice dated April 2 issued by the Wenquan branch of the Xianning Public Security Bureau. On October 19, 2011, the Xianning Intermediate People’s Court reportedly tried Gao for “inciting subversion,” but the court did not announced a verdict. Gao was then released on bail on February 15, 2012, with a verdict in his case still unannounced. Prior to his detention, Gao had been an active online discussant about China’s human rights situation.

- Li Shuangde (李双德), a citizen lawyer and activist based in Chengdu City, Sichuan Province, was sentenced on June 1, 2011, to four months in prison and fined 20,000 yuan for “credit card fraud” by the Jinjiang District Court in Chengdu City, Sichuan Province. He was released on July 22, after completing his sentence, which included time served following his criminal detention on March 24. Li was the first activist arrested during the crackdown known to be convicted of a crime and sentenced to prison. He was detained on suspicion of “credit card fraud” by the Public Security Bureau (PSB) of Jinjiang District and formally arrested on the same charge on April 2 after police had taken him away on March 21. His arrest and conviction came despite the fact that his family repaid the 20,000 yuan owed by Li to his bank by April 2. Li has operated a legal aid center in Chengdu, providing legal aid to citizens who cannot afford to hire a lawyer. Li had been harassed on numerous occasions in the past by local officials.

- Liang Haiyi (梁海怡, aka Miaoxiao [渺小]), a netizen originally from Guangdong Province, was taken in for questioning on February 20, 2011, by police in Harbin City, Heilongjiang Province, along with her ex-husband, who was later released. On February 22, Liang was criminally detained on suspicion of “inciting subversion of state power” and subsequently arrested. Police accused her of “posting information from foreign websites regarding ‘Jasmine Revolution’ actions on domestic websites.” By August, it was reported that her case had been transferred to the Harbin Intermediate People’s Court for prosecution but that the court did not issue a decision. Friends and family members of Liang revealed in January 2012 that, when they went to visit her at the Harbin Women’s Detention Center in October 2011, they were told Liang was no longer being held there, and so her whereabouts remained unknown. It was eventually revealed in July 2014 that she had been released from the detention facility in May 2012 and returned to her home in Conghua, Guangdong, where she was placed under residential surveillance. On July 18, 2014, a day after her residential surveillance was lifted, she was sentenced to two years’ imprisonment, suspended for three years for “inciting subversion of state power” by the Conghua City People’s Court, entrusted by the Harbin court. Very little was known about Liang’s circumstances in police custody, though it is known that authorities repeatedly asked her to confess to her crimes, but that she refused. Similarly, very little is known about her conditions under residential surveillance, except that she was give 1,500 yuan a month from her work unit to cover living expenses. Lawyer Liang Xiaojun (梁小军) was interested in representing Liang after she was first detained, but her family did not give its authorization, so the attorney did not get involved in the case. During her sentencing in July 2014, Liang was represented by Liao Jianhao (廖剑豪).

- Ni Yulan (倪玉兰), a housing rights activist and former lawyer, was criminally detained in Beijing for “creating a disturbance,” according to a detention notice dated April 6, 2011, for hanging a banner outside the Yuxinyuan Guest House, her residence at the time. Ni and Dong disappeared around that date, and family members only discovered their whereabouts on April 11 after contacting the police. She was formally arrested as of May 17. On July 13, her case was transferred to the procuratorate for review, and with an additional charge of “fraud” for allegedly saying she was a lawyer in order to win sympathy for her case and to profit. Her case went sent back to public security for further investigation on August 2. Ni and her husband, Dong Jiqin, had their case heard by the Xicheng District People’s Court on December 29, 2011, but no verdict was announced. On April 10, 2012, the court announced that Ni was guilty of both “creating a disturbance” and “fraud,” and sentenced her to 32 months in prison. On July 27, the Beijing No. 1 Intermediate Court held an appeal hearing and dismissed the charge of fraud against Ni and also reduced her original sentence by two months. Ni was held in the Xicheng District Detention Center in Beijing’s Haidian District before being transferred to Beijing Women’s Prison to serve our her sentence. Ni was released from prison on October 5, 2013, after completing her sentence, and returned home with her husband. Suffering from numerous illnesses, Ni faced a long period of recovery. This was the third time that Ni has been detained for an extended period by Beijing police. As the result of repeated episodes of torture over the past decade, Ni cannot walk and suffers from an assortment of chronic medical issues, including difficulty breathing, heart problems, and digestive trouble. During her detention, Ni’s lawyer submitted unsuccessful requests to have Ni released on medical grounds.

- Ran Yunfei (冉云飞), a writer, blogger, and activist from Chengdu, Sichuan Province, was formally arrested on March 25, 2011, for “inciting subversion of state power.” He was held in Dujiangyan Detention Center in Sichuan before being released on August 9 and sent home to serve six months of “residential surveillance,” during which Ran was prohibited from giving media interviews and making public statements. Ran went into police custody on February 20, when he was summoned to “tea.” Officers later searched his home and confiscated his computer. Ran was criminally detained for “subversion of state power” on February 24, according to a police detention notice; it is not known why the charge was changed. Ran, a member of the ethnic Tu minority who studied Chinese literature at Sichuan University, had been employed by the magazine Sichuan Literature. He is a prolific writer of social and political commentary and maintains a blog at <http://www.bullogger.com/blogs/ranyunfei/>.

- Wang Lihong (王荔蕻), a Beijing-based human rights defender and democracy activist, was criminally detained for “creating a disturbance” on March 21, 2011, and formally arrested on April 21. The charge against her was later changed to “gathering a crowd to disrupt traffic order,” and in mid-July a local procuratorate approved her case for prosecution, but under the original charge of “creating a disturbance.” On August 12, trial proceedings opened and then concluded after two-and-a-half hours, and the Chaoyang District People’s Court announced on September 9 that Wang had been convicted on the charge and sentenced to nine months in prison. According to her attorneys, the proceedings were marred by many procedural flaws and the case itself has all along been rife with errors in the investigation and indictment stages. The Beijing No. 2 Intermediate People’s Court upheld the original verdict at an appeal hearing on October 20. Wang was released at the end of her sentence, on December 20, 2011. Upon her release, Wang was in poor health, having lost a great deal of weight while struggling with heart and blood pressure problems and pain in the lower back. Before she was released, Wang staged a 3-day hunger strike to protest the use of torture in the Chaoyang District Detention Center; she said that detainees there are required to sit motionless in an awkward position for five hours every day, which causes hip pain for those held for long periods of time. The “creating a disturbance” charge against Wang was tied to her support for the “Fujian Three” netizens who were convicted of slander in 2010, and in particular to the large crowd of netizens who, along with Wang, gathered in peaceful protest outside their sentencing hearing on April 16, 2010. On May 13, 2011, her lawyer, Liu Xiaoyuan (刘晓原), applied for her release on bail prior to her trial, but this request was rejected. In 1989, Wang joined the pro-democracy demonstrations in Beijing, an experience which led her to resign from her government job in 1991. Wang, a former doctor, then became a dedicated democracy activist and human rights defender. She has worked on projects such as relief efforts for the “Tiananmen homeless” and advocated on behalf of citizens fighting land seizures in Beihai City, Guangxi Province.

- Xue Mingkai (薛明凯) was formally arrested for “inciting subversion of state power” but later reportedly convicted of “subversion,” a more serious crime, and sentenced to four years in prison. Details of the case, including trial date and location, and specific evidentiary basis for charging and convicting Xue, are unclear at the time of writing. Xue was held at the Jining City Detention Center in Shandong before reportedly being sent to Shandong Provincial No. 1 Prison on March 12, 2012, to serve his sentence. The date of Xue’s arrest also remains unknown, and his parents have reportedly not received a formal detention or arrest notice since he was seized in February of 2011 in Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province. Xue’s father believes Xue was returned to Jining from Hangzhou around March 7 or 8, 2011. His mother repeatedly inquired at Jining government offices before learning of her son’s whereabouts, and she has been denied many requests to see Xue in detention. She was seized on April 20, 2011, outside of the Jining Letters and Visits Office and also has been beaten for petitioning over Xue’s previous imprisonment. Xue served 18 months in prison between May 2009 and November 2010 for “subversion of state power.” A migrant worker living in Shenzhen at that time, Xue was charged with “subversion” after allegedly planning to organize a political party called the “China Democratic Workers’ Party” with online friends in the summer of 2006 and then contacting and joining an overseas democracy organization in early 2009.

- Zhu Yufu (朱虞夫), a Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province-based democracy activist, was taken away by police on March 5, 2011. Officers also searched his home and confiscated two computers and other items. Zhu was criminally detained on suspicion of “inciting subversion of state power”and formally arrested on the same charge on April 11. In July, his wife appealed to authorities to release Zhu on bail due to his longstanding poor health, but her request was rejected. On October 25, the Shangcheng County People’s Court approved an application from the local procuratorate to dismiss charges of “inciting subversion of state power” against Zhu, fueling speculation that he would soon be set free. However, police sent the case back to the procuratorate in late December, with Zhu still in detention. His lawyer visited Zhu in detention in mid-January of 2012 in order to prepare a new defense case for his client. The Hangzhou City Intermediate People’s Court held trial proceedings on Zhu’s case on January 31, 2012, but did not announce a verdict that day. On February 10, the court announced that Zhu was guilty of “inciting subversion” and sentenced him to seven years’ imprisonment with a subsequent three years’ deprivation of political rights. Zhu was transferred from the Shangcheng Detention Center to Zhejiang Provincial No. 4 Prison on May 10, 2012, after his appeal of his conviction had been rejected by the Hangzhou City High People’s Court. Formerly a property manager at the Hangzhou City Shangcheng District Urban Housing Bureau, Zhu was convicted of “subversion of state power” in 1999 and served seven years in prison for founding the Opposition Party magazine, which carried articles about the China Democratic Party. After his release in 2006, he spoke out against the torture he suffered in prison and continued to promote democratization. He was detained again in 2007 after a confrontation with a police officer who was questioning his son, and sentenced to two years in prison for “beating police and hindering public duty.”

Re-education through Labor (RTL)

- Cheng Li (成力) was a 57-year-old Beijing-based performance artist at the time he was detained on March 23, 2011, three days after performing a piece entitled “Art Whore” during a performance art exhibition at the Beijing Museum of Contemporary Art. The theme of the show was “sensitive areas,” and two other artists were also seized by police after the exhibition. Cheng was later criminally detained for “causing a disturbance” by officers from Songzhuang Police Station in Beijing, and was then sent to one year of RTL.

- Hua Chunhui (华春晖) is a Wuxi City, Jiangsu Province-based netizen, activist, and mid-level manager at an insurance company. He was seized by police on February 21, 2011, and criminally detained on suspicion of “endangering state security,” according to a notice issued by police at Tanduqiao Station in Wuxi’s Nanchang District. CHRD learned in mid-April 2011 that Hua was sent to RTL for 18 months. Due to health reasons, however, Hua was ordered from August 10 to serve the punishment outside of his home, and he was warned not to leave Wuxi. Hua, using the Twitter account @wxhch64, tweeted messages about the “Jasmine Revolution.” Hua and his fiancée, Wang Yi (王译), have been active in civil society initiatives in recent years; for example, the couple organized a forum in Beijing in May 2010 to discuss the demonstrations taking place outside the trial of three netizens in Fujian Province. Wang Yi (whose given name is Cheng Jianping) was sent to one year of RTL in November 2010 for a tweet she posted during violent anti-Japan demonstrations the prior month.

- Huang Chengcheng (黄成诚), a Chongqing resident initially detained on March 19, 2011,was issued two years of RTL by the Chongqing City RTL Committee on April 18, 2011, for allegedly sending out “Jasmine”-related messages online. According to the RTL decision, Huang was punished for “inciting subversion of state power” for messages he posted from February 20 to March 17 inviting others to meet him around the Chongqing People’s Liberation Monument, where he would be carrying flowers or drinking “jasmine tea.” After taking Huang into custody, Bishan District Public Security officers questioned him continuously for three days, during which time he was slapped and had boiling water splashed on him, but still maintained his innocence. He was held at the Xishanping RTL facility in Chongqing. In early August 2011, authorities dismissed an administrative appeal of his punishment as well as a lawsuit, both of which had been submitted by Huang’s family. Huang had previously served three years in prison for “inciting subversion” for writing an article in 2004 calling on Chinese youth to not accept the “imprisonment of Communist ideology.” RTL authorities added one week to Huang’s punishment in the summer of 2012 on the grounds of “poor performance” in forced labor, as Huang was unable to complete a mounting number of tasks in part due to a worsening hand injury suffered in RTL. Huang was eventually released on December 18, 2012, several months before his punishment was due to expire.

- Yang Qiuyu (杨秋雨), a Beijing-based dissident, was taken away on March 6, 2011. He was criminally detained on March 7 on suspicion of “creating a disturbance,” and on March 9 police returned to search his home, confiscating a computer, name cards, and other items. Yang’s wife received a notice from Beijing PSB Dongcheng Sub-division on April 14 that Yang had been sent to RTL for two years.

- Yu Yunfeng (于云峰), an activist from Heilongjiang Province, was issued a two-year RTL punishment after being taken into custody by Harbin Public Security officers on July 29, 2011, when he was being questioned by police for a third time in 11 days. He is reportedly being punished for alleged offenses related to “inciting subversion of state power” for “spreading rumors against the Party and against socialism.” In May 2011, Yu was given 10 days of administrative detention for “disrupting public order” after giving a speech near Harbin’s Flood Control Monument. In recent years, Yu has become active in rights defense efforts such as evictions and demolitions, and in support of freedom of online speech and political reforms. Friends and family members have indicated that as recently as December 2011 Yu was suffering both physically and emotionally while serving his punishment in the Wanjia RTL camp in Harbin.

Other Criminal Detentions

- Cao Jinbai (曹劲柏), a netizen from Zaoyang City, Hubei Province, attended the February 20 “Jasmine gathering” at Beijing’s Wangfujing Shopping Street and later wrote a post about his experience which he circulated via Skype. On February 24, 2011, police in Beijing detained Cao, searched his home, and confiscated his computer, cell phone, and other personal items. Cao was released on March 1, only to be detained again on March 7 for a few hours and again on March 15 for six days. Police told Cao that he was being “released on bail awaiting trial,” but never informed him what charge he was accused of or presented him with any formal documentation about his repeated detentions.

- Cheng Wanyun (程婉芸), is a Beijing-based netizen originally from Sichuan Province. She was summoned by Beijing police on February 26, 2011, and criminally detained for “creating a disturbance” and “obstructing public safety” the next day. Her computer was also confiscated. On March 28, Cheng was released on “bail awaiting trial” and ordered to serve one year of “public surveillance” (guanzhi). During her detention in Tongzhou District Detention Center, Cheng was interrogated seven times, mainly about her writings on QQ groups about the revolutions in the Middle East, and whether she has been “exploited by someone else” or been part of a wider network or organization.

- Feng Xixia (封西霞), a petitioner from Xi’an City, Shaanxi Province, was criminally detained in late February 2011 and tortured while in detention. Feng was seized in Beijing on February 27 and detained first in the Fengtai District Detention Center, where she reportedly was handcuffed in an uncomfortable position and beaten. She was transferred to the Beijing Number 1 Detention Center on March 3 and released on “bail awaiting trial” on March 25. Police also searched the residence Feng had rented in Beijing, confiscating her computer and other items. Officials never provided Feng with any formal documentation regarding her detention.

- Gu Aisi (贾爱思), a Shanghai petitioner, was seized in Beijing on April 29, 2011. Gu had traveled to Beijing with more than 1,000 fellow Shanghai petitioners to demonstrate outside the National Letters and Visits Bureau. Gu was returned to Shanghai and criminally detained before being released on May 7.

- Guo Gai (郭盖), a Beijing-based artist, was seized on April 24, 2011, after taking photos at a performance art exhibition at the Beijing Museum of Contemporary Art on March 20, where some of the pieces touched on the ongoing crackdown. Guo, whose computer was confiscated, was later criminally detained but the precise charge is unknown. Guo was held in the Taihu Detention Center in Beijing’s Tongzhou District before being released on “bail awaiting trial” on April 24.

- Guo Weidong (郭卫东), an employee of a business corporation and active netizen from Haining City, Zhejiang Province, was criminally detained on March 11, 2011, for “inciting subversion of state power.” The day before, police had arrived at Guo’s home and office and confiscated his computer along with other items. Guo had previously been summoned twice for questioning in relation to the anonymous online calls for “Jasmine Revolution” protests. Guo was released on “bail awaiting trial” on April 10.

- Guo Yigui (郭谊贵), a Shanghai-based petitioner, together with fellow petitioners Tan Lanying and Yang Lamei (杨腊梅), was seized on February 20, 2011, and held on suspicion of “assembling a crowd to disrupt the order of a public place.” Guo was released on February 25, while Tan and Yang were released on March 23. The three, all veteran petitioners, were separately taken into custody by police at a site in Shanghai identified in online postings calling for “Jasmine Revolution” protests, though there is no indication the three knew anything about the protests.

- Huang Xiang (黄香), a Beijing-based artist, was seized together with fellow artists Cheng Li and Zhui Hun after appearing in a performance art exhibition at the Beijing Museum of Contemporary Art on March 20, 2011, where some of the pieces touched on the ongoing crackdown. Huang was later criminally detained for “creating a disturbance” by officers from Songzhuang Police Station in Beijing. Huang was held at Taihu Detention Center in Beijing’s Tongzhou District before being released on “bail awaiting trial” on April 24.

- Kan Siyun (阚思云), a petitioner from Chengdu City, Sichuan Province, was seized on April 9, 2011, outside of the sentencing hearing of Sichuan-based activist Liu Xianbin (刘贤斌). Together with two other petitioners, Li Renyu and Peng Tianhui, the three were originally returned to Chengdu City from Suining City and given seven days of administrative detention on March 28; however, instead of being released, they were then criminally detained by the Chengdu City PSB and transferred to the Chengdu City Detention Center. They were charged with “inciting subversion of state power” and released on April 24 on “bail awaiting trial.”

- Lan Jingyuan (兰靖远), a Beijing-based victim of forced eviction who has been petitioning the government for compensation, was detained on February 24, 2011, on suspicion of taking part in an “illegal demonstration” after participating in the “Jasmine Revolution” protest around Wangfujing in Beijing on February 20. Lan was released on “bail awaiting trial” on February 24.

- Li Hai (李海), a Beijing-based dissident and activist, was criminally detained on February 26, 2011, by police in Chaoyang District for “creating a disturbance.” Li was released on “bail awaiting trial” on April 6. He was a student leader at Beijing University during the 1989 pro-democracy demonstrations, and was expelled from school and detained for seven months after the demonstrations were suppressed. In 1995, Li was detained and eventually sentenced to nine years in prison for his pro-democracy activities and advocacy on behalf of victims of the Tiananmen Massacre. Following his release in 2004, Li continued his activism and has been repeatedly harassed, threatened, and detained by authorities.

- Li Renyu (李仁玉), a petitioner from Chengdu City, Sichuan Province, was seized on April 9, 2011, outside of the sentencing hearing of Sichuan-based activist Liu Xianbin (刘贤斌). Together with two other petitioners, Peng Tianhui and Kan Siyun, Li was originally returned to Chengdu City from Suining City and given seven days of administrative detention on March 28; however, instead of being released, they were then criminally detained by the Chengdu City PSB and transferred to the Chengdu City Detention Center. They were charged with “inciting subversion of state power” and released on April 24, 2011, on “bail awaiting trial.”

- Li Xiaocheng (李小成) is a Beijing-based petitioner-activist originally from Henan Province. On February 20, 2011, Li went to Beijing’s Wangfujing area, one of the locations identified in the call for “Jasmine Revolution” protests. Li was seized in Beijing on February 26 and detained in Fangshan Detention Center, the Beijing Number 1 Detention Center, and later the Fangshan Detention Center again. On March 27, he was released on “bail awaiting trial.” Police never presented Li with any formal documentation which might explain his detention. Li is a veteran petitioner known as the “chief” of Beijing’s “Petitioners Village,” an area near the Beijing South Train Station where petitioners congregate.

- Li Yongsheng (李永生), 45, a Beijing-based rights activist, was criminally detained on March 7, 2011, for “creating a disturbance” by the Tongzhou District PSB. He was released on “bail awaiting trial” and returned home on April 6. Li has participated in a number of activities organized by NGOs in Beijing in recent years.

- Liu Guohui (刘国慧) is a victim of forced eviction and petitioner from Linyi City, Shandong Province. Liu was seized on March 10 when she went to a meet with a policeman in Linyi City who promised to discuss compensation issues regarding her demolished home. She was then criminally detained on March 11, 2011, on suspicion of “inciting subversion of state power.” On April 8, Liu was released on “bail awaiting trial” and placed under six months of residential surveillance, which was lifted on September 28, 10 days before it was scheduled to expire. While in detention, Liu was questioned about her discussion online with another activist about the Jasmine Revolution as well as information about “barefoot” lawyer and activist Chen Guangcheng (陈光诚), about whom the police alleged that Liu “sent information to anti-China forces.” Liu has filed a complaint over her time in detention and residential surveillance to several bodies in Linyi.

- Liu Huiping (刘慧萍), a petitioner from Guangxi Province, was criminally detained on suspicion of “inciting subversion of state power” after being forcibly returned to Nanning City, Guangxi Province from Beijing on March 15, 2011. Liu was released on “bail awaiting trial” in early April. Liu is a leader of a group of female village activists who have been petitioning against gender discrimination against women who were married to men from other villages and consequently lost their right in the management of economic affairs of villages around Nanning.

- Liu Zhengxing (刘正兴, aka Zhui Hun [追魂]), is a Beijing-based artist. Zhui was seized together with artists Cheng Li and Huang Xiang after appearing in a performance art exhibition at the Beijing Museum of Contemporary Art on March 20, 2011, where some of the pieces touched on the ongoing crackdown. Zhui was later criminally detained for “causing a disturbance” by officers from Songzhuang Police Station in Beijing. Liu was held in the Taihu Detention Center in Beijing’s Tongzhou District before being released on “bail awaiting trial” on April 24.

- Mo Jiangang (莫建刚), a longtime human rights and democracy activist, was seized sometime before March 6, 2011, and criminally detained. As of March 18, he had been released. Mo, who was born in Guiyang City, Guizhou Province, moved to Beijing and became involved in the pro-democracy movement in 1978. He was briefly detained after taking part in the 1989 demonstrations in Beijing. After 1989, Mo returned to Guiyang and continued his activism, becoming a leader among local democracy activists.

- Pan Zhenjuan (潘振娟), a petitioner from Guangxi Province, was taken into custody and subsequently released.

- Peng Tianhui (彭天惠), a petitioner from Chengdu City, Sichuan Province, was seized on April 9, 2011, outside of the sentencing hearing of Sichuan-based activist Liu Xianbin (刘贤斌). Together with two other petitioners, Li Renyu and Kan Siyun, the three were originally returned to Chengdu City from Suining City and given seven days of administrative detention on March 28; however, instead of being released, they were then criminally detained by the Chengdu City PSB and transferred to the Chengdu City Detention Center. They were charged with “inciting subversion of state power” and released on April 24 on “bail awaiting trial.”

- Quan Lianzhao (全连昭), a petitioner from Guangxi Province, was seized by interceptors in Beijing on February 26, 2011, and forcibly returned to Nanning City, Guangxi Province, where she was criminally detained for nearly a month on suspicion of “subversion of state power.” Quan was held in the Nanning City No. 1 Detention Center. It is believed that Quan’s detention was related to her taking part in a “Revolutionary Singing Gathering” in a Beijing park on February 3, where petitioners gathered to sing revolutionary songs and present accounts of their grievances. Quan also gathered with a number of petitioners on February 20 to present their grievances at Beijing’s Chaoyang Park; while the gathering drew the attention of police because it was the same date as the proposed “Jasmine Revolution” protests, friends said that Quan does not use the Internet and would have not known of the demonstrations called for that date. Quan has been petitioning for four years in response to the forced expropriation of land in her village.

- Sun Desheng (孙德胜), a Guangzhou City, Guangdong Province resident, was criminally detained on suspicion of “inciting subversion of state power” at some point before March 9, 2011, and was released on bail in July. Reportedly, Sun’s detention stemmed from a friend’s dinner party, where Sun wrote anti-corruption and anti-dictatorship slogans and then posed with friends for a picture. The dinner, which took place on February 15, was also attended by lawyers Liu Shihui (刘士辉) and Li Fangping (李方平). Liu’s home was searched on February 24, and police discovered the photograph on his computer.

- Tan Lanying (谈兰英), a Shanghai-based petitioner-activist, was criminally detained for “gathering a crowd to disrupt the order of a public place” on February 21, 2011. Tan was released on March 23. Tan, together with veteran petitioners Yang Lamei and Guo Yigui, were separately taken into custody by police at a site in Shanghai identified in online postings calling for “Jasmine Revolution” protests, though there is no indication the three knew anything about the protests. Tan has been petitioning for 17 years, seeking redress for grievances related to the forced demolition of her home.

- Wei Qiang (魏强), a human rights activist, was seized in Beijing on February 26, 2011, and detained in several detention centers in Beijing until March 21, when he was returned to his hometown of Yan’an City. He was again detained in Yan’an, where police issued both a detention notice for “creating a disturbance” as well as a notice that Wei was to be sent to two years of RTL. At the end of March, however, Beijing police once again returned Wei to the capital, where he was detained in an unknown location for 22 or 23 days. At this place, Wei was held in solitary confinement and chained to a chair except for six hours during which he was allowed to sleep. One time when Wei felt ill and was not able to wake up after six hours, guards stomped on him and beat him. Wei was then once more taken back to Yan’an, where the head of the police used his knee to knead on his spine, injuring Wei’s waist. On April 30, Wei was released on “bail awaiting trial.” Wei, originally from Xi’an City, Shaanxi Province, moved to Beijing in 2010. On February 20, he used his Twitter account (@Watchmen725) to report from the scene in front of the Wangfujing McDonald’s, one of the locations identified in the call for “Jasmine Revolution” protests.

- Wei Shuishan (魏水山), a Zhejiang Province-based dissident and member of the banned China Democracy Party, was criminally detained on March 5, 2011, though Wei’s family as of the summer of 2011 had not received a formal detention notice. (As of early 2013, CHRD had not received further information about Wei’s situation or whereabouts.)

- Weng Jie (翁杰), a Beijing resident, was criminally detained for “creating a disturbance” on March 2, 2011. Weng had been present at a Beijing site picked for “Jasmine Revolution” protests on February 20 and was later seized by police. Weng was detained in the Chaoyang District Detention Center until March 25, when he was released on “bail awaiting trial.”

- Xie Qingguo (谢庆国), a Shanghai petitioner, was seized in Beijing on April 29, 2011. Xie had traveled to Beijing with more than 1,000 fellow Shanghai petitioners to demonstrate outside the National Letters and Visits Bureau. Xie was returned to Shanghai and criminally detained before being released on May 7.

- Yang Lamei (杨腊梅), a Shanghai-based activist, was seized on February 20, 2011, and held on suspicion of “gathering a crowd to disrupt the order of a public place” together with fellow petitioners Tan Lanying and Guo Yigui. Yang was released on March 23. The three, all veteran petitioners, were separately taken into custody at a site in Shanghai identified in online postings calling for “Jasmine Revolution” protests, though there is no indication the three knew anything about the protests.

- Yang Yong (杨勇), a Zhejiang-based netizen, was taken away by police on April 1, 2011, and later criminally detained. It is believed that Yang, whose Twitter account is @think9, was detained because he spread information via Twitter about the “Jasmine” protests. Yang was held in the Jiaxing City Detention Center, where he was reportedly subjected to abuse, before being released on April 22 on “bail awaiting trial.”

- Yao Yuping (姚玉平), a Shanghai petitioner, was seized in Beijing on April 29, 2011. Yao had traveled to Beijing with more than 1,000 fellow Shanghai petitioners to demonstrate outside the National Letters and Visits Bureau. Yao was returned to Shanghai and criminally detained before being released on May 7.

- Zhang Jiannan (张健男), better known by his online name, Secretary Zhang (张书记), was seized at his home in Beijing on March 2, 2011, and criminally detained for taking part in an “illegal demonstration.” Zhang was released on “bail awaiting trial” on April 1. Zhang was the founder of the website 1984 BBS, an online discussion forum dedicated to discussion of current events and the publication of censored news, which was shut down by the government on October 12, 2010. His twitter account is @SecretaryZhang.

- Zhang Yanhong (张燕红), a Shanghai petitioner, was seized in Beijing on April 29, 2011. Zhang had traveled to Beijing with more than 1,000 fellow Shanghai petitioners to demonstrate outside the National Letters and Visits Bureau. Zhang was returned to Shanghai and criminally detained before being released on May 7.

- Zheng Chuangtian (郑创添), a human rights activist, was criminally detained for “inciting subversion of state power” by police in Huilai County, Jieyang City, Guangdong Province on February 26, 2011. Officers also searched Zheng’s home. On March 28, Zheng was released on “bail awaiting trial” and returned home to Huilai.

- Zheng Peipei (郑培培), a Shanghai petitioner, was seized in Beijing on April 29, 2011. Zheng had traveled to Beijing with more than 1,000 fellow Shanghai petitioners to demonstrate outside the National Letters and Visits Bureau. Zheng was returned to Shanghai and criminally detained before being released on May 7.

- Zhang Yongpan (张永攀), a Beijing-based legal activist, was criminally detained for “creating a disturbance” between April 14 and May 13, 2011, and later released on “bail awaiting trial.” His detention is believed to have been in retaliation for his online support for activist Wei Qiang, who disappeared into police custody in February.

Involuntary Psychiatric Detentions

- Hu Di (胡荻), a Beijing-based netizen and writer, went missing on March 13, 2011, and was found, in August, to be held in the Hefei No. 4 Hospital, a psychiatric institution, and he was then released by early September. According to netizens who visited him after his release, Hu was in “good shape.” However, details about his disappearance and his detention in the psychiatric institution remain unclear. Netizen Zheng Tao (郑涛, aka @LuoFee [罗非]) went to the hospital on August 19 and, while accompanied by a doctor, saw Hu for a very short time before the doctor demanded Zheng leave and finally dragged him away. Zheng reported that Hu was in good spirits but had grown thin, and that Hu indicated he’d been held in the hospital for more than 10 days. It remains unknown why Hu was being held at the institution or whether his family could visit him.

- Qian Jin (钱进), a pro-democracy activist from Bengbu City, Anhui Province, was forcibly held in the Anhui Huaiyuan Rongguang Hospital, a psychiatric facility, from February 26, 2011, until his release on June 29, several weeks after authorities reportedly indicated he would be able to go home. Following his release, Qian—who does not suffer from mental health problems—was in good spirits and discussed in detail his experiences in the facility. He was seized by Bengbu national security police on February 25, when a group of police officers escorted him to his home and confiscated his computer, and he was taken to the hospital the next day. In mid-June, Qian was despondent during a visit by his sister since he had already been detained for more than three months and the “sensitive” date of June 4 had passed, yet he still had not been released. The two previous times officials had illegally detained Qian in a psychiatric hospital, he was released after three months.

Illegal Residential Surveillance

- Ai Weiwei (艾未未), a prominent Beijing-based artist and activist, was released on bail on June 22, 2011, after being held under illegal residential surveillance by police at an unknown location since early April. His wife, Lu Qing (路青), was able to visit him on May 15, which had been the first time Ai had been seen since he was seized by police at Beijing’s Capital International Airport and prevented from boarding a flight to Hong Kong on the morning of April 3. At that time, police searched Ai’s studio in Beijing, confiscating all computers and hard drives, and said that he was under investigation for “economic crimes.”

- Tang Jingling (唐荆陵), a human rights lawyer originally from Hubei Province but living in Guangzhou, was taken into custody on February 22, 2011, on suspicion of “inciting subversion of state power,” and then placed under residential surveillance in early March at the Dashi Police Training Center (大石民警培训中心) in Guangzhou’s Panyu District. He was eventually released on August 1 and sent back to his hometown in Hubei Province, and was not allowed to return to Guangzhou or see his wife, who was still residing in that city. “Residential surveillance” is a form of pre-trial detention. According to Article 57 of China’s Criminal Procedural Law (CPL), a suspect under residential surveillance must be held either at home or at a designated dwelling if they have no permanent residence. Detaining Tang, who has a home in Guangzhou, in another location therefore breaches this legal provision. During Tang’s detention, attempts to contact or visit his wife, who had been intimidated and periodically restricted in movement, had failed. Policemen also had guarded his apartment and stopped anyone trying to enter. Upon Tang’s release, his wife indicated that the surveillance around her home had been lifted that same day.

- Wu Yangwei (吴杨伟, aka Ye Du), Guangzhou-based author and activist, was placed under residential surveillance in Panyu County, Guangdong Province for “inciting subversion of state power” on March 1, 2011, after originally being taken away from his home on February 22. On March 2, police escorted Ye back to his home in Guangzhou, where they confiscated a computer, CD-ROMs, USB drives, books, documents, and other items, then took him away again. According to Article 57 of China’s Criminal Procedural Law (CPL), a suspect under residential surveillance must be held either at home or at a designated dwelling if they have no permanent residence. Detaining Ye, who has a home in Guangzhou, in another location therefore breaches this legal provision. Sometime in May, Wu was said to be back home but was being barred from contacting anyone and living under close police monitoring.

Enforced Disappearances

- Gu Chuan (古川), a Beijing-based author and human rights activist, was missing between February 19 and April 22, 2011. On February 19, about twenty Beijing policemen searched Gu’s home without presenting their police IDs or a search warrant. They confiscated two computers, two cell phones, and some books. When Gu’s home was searched, the policemen said the search was related to Gu using Twitter to repost messages about the “Jasmine Revolution.”

- Hu Mingfen (胡明芬), accountant of prominent artist and activist Ai Weiwei, was missing between April 8 and about June 24, 2011.

- Jiang Tianyong (江天勇), a Beijing-based human rights lawyer, was missing between February 19 and April 19, 2011. According to Jiang’s wife, he appeared to be in decent condition when he returned home. On the afternoon of February 19, Jiang was seized from his brother’s home and driven away by men identified by his family as Beijing policemen. Police returned that evening and confiscated Jiang’s computer. The police never presented police IDs or any search or detention warrants at any point during the proceedings.

- Jin Guanghong (金光鸿), a Beijing-based lawyer with the Beijing Jingfa Law Firm, disappeared on April 8 or 9, 2011, and returned home on April 19. Two months later, he was forcibly taken from his rental home in Beijing and abandoned in Hebei Province, most likely by public security personnel intent on limiting his activities in the run-up to the 90th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party on July 1. Jin is one of the few of those disappeared during the crackdown to publicly acknowledge being tortured. CHRD learned that Jin was held first in a detention center and then moved to a psychiatric hospital. While in the psychiatric hospital, he was beaten by unidentified individuals, tied to a bed, given injections of unknown substances, and forced to ingest unidentified medicine.

- Lan Ruoyu (蓝若宇), a Chongqing-based graduate student, went missing on February 27, 2011, and was reportedly released later, though CHRD has not been able to independently confirm this information. Police also had confiscated a computer belonging to Lan, a student at Communication University of China.

- Li Fangping (李方平), a Beijing-based human rights lawyer, was kidnapped outside the offices of Yirenping, an anti-discrimination NGO, on April 29, 2011. Li was able to briefly speak with his wife, telling her, “I may be gone for a period of time…can’t talk more.” He was released on May 4.

- Li Tiantian (李天天), a Shanghai-based human rights lawyer, disappeared between February 19 and May 24, 2011. After her release, CHRD learned that Li was taken from her home in Shanghai by police, who also searched the residence and confiscated two computers. Following a day of police questioning, she was taken to a guesthouse in an unknown location and placed under “residential surveillance.” She returned to her hometown in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region upon her release. Li maintains a blog (http://blog.sina.com.cn/u/1896094822) and her Twitter account is @litiantian.

- Li Xiongbing (黎雄兵), a Beijing-based human rights lawyer, went missing on the morning of May 4, 2011. He returned on May 6. Li has represented political and human rights activists, including Yang Chunlin (杨春林) and Yuan Xianchen (袁显臣), victims of religious persecution and discrimination, as well as groups including the former NGO Gongmeng, which Li represented in its in its dealings with tax officials in 2009. Li also serves as a legal adviser to health rights NGO Aizhixing.

- Liu Anjun (刘安军), a Beijing-based human rights activist, was seized outside of his home on February 18, 2011, by a group of officials, including local police and national security officers. The officers, after beating and kicking him, forcibly took him to a rural area outside of Beijing where he was guarded by local villagers who were being paid 50 RMB a day and given food and drink by local officials. Liu added that officers confiscated his two cell phones and stole 300 RMB from him. Liu went on a 10-day hunger strike to protest his illegal detention and, as a result, was taken to a hospital on March 18, where he remained under guard until he was freed. Local officials who visited him during his detention told him to “shut up and mind his own business.” He was freed after 45 days of enforced disappearance. Liu believes that his detention is related to an interview he gave on February 16 to Radio Free Asia about the jasmine revolution in North Africa.

- Liu Dejun (刘德军), a Beijing-based netizen, was missing between February 27 and May 13, 2011. During that period, police went to the Wuhan City home of Liu’s sister on three occasions to search her computer as well as items left there by Liu. Officers did not provide any legal notification regarding Liu’s disappearance on any of these occasions, and officers in Beijing and Wuhan contacted by the family refused to provide any information about Liu’s whereabouts.

- Liu Shihui (刘士辉), a Guangzhou-based human rights lawyer, went missing on February 20, 2011, and then was sent back home on June 12, having been released on bail after being charged with “inciting subversion of state power.” Before he disappeared, Liu was brutally beaten by a group of unidentified individuals while waiting at a bus stop to participate in the February 20 “Jasmine Revolution” protests in Guangzhou. In August, Liu spoke for the first time about torture that he suffered during the time his whereabouts were unknown.

- Liu Xiaoyuan (刘晓原), a Beijing-based human rights lawyer with the Beijing Qijian Law Firm, went missing between April 14 and 19, 2011. Liu, a friend of Ai Weiwei’s, had indicated his willingness to defend the artist-activist before he disappeared. After Liu reappeared, he told The Guardian that he did not want to give any details about what had happened to him during his disappearance.

- Liu Zhenggang (刘正刚), a designer who works for artist-activist Ai Weiwei, was released from an enforced disappearance by June 24, 2011, after going missing around April 12. He reportedly had a heart attack while under interrogation and was admitted to a hospital for treatment after his release.

- Liu Zhengqing (刘正清), a Guangzhou-based human rights lawyer with the Guangdong Fulin Guotai Law Firm, went missing on March 25, 2011. During his disappearance, Liu’s home was raided three times and police took away computers, printers, and other personal belongings. He reappeared on April 29. He has represented Falun Gong practitioners and human rights activists. He was released on “bail awaiting trial” on suspicion of “inciting subversion of state power.”

- Tan Yanhua (谭艳华), a Guangzhou City-based human rights activist, went missing on February 25, 2011, and was released from police custody on an unknown date.

- Tang Jitian (唐吉田), a Beijing-based human rights lawyer formerly with the Beijing Anhui Law Firm before his license to practice law was revoked in 2010, was seized on the evening of February 16, 2011, after attending a lunch meeting with activists to discuss how they might provide assistance to human rights defender Chen Guangcheng and his family. After Tang was held incommunicado for three weeks, he was sent back to his hometown in Jilin Province. In very poor health, Tang was put under “soft detention” in his home. Authorities warned him and his family not to speak out and to have no contact with the outside world.

- Teng Biao (滕彪), a Beijing-based human rights lawyer, was missing for 70 days, between February 19 and April 29, 2011. Teng Biao’s wife, who confirmed his return, said at the time that she could not comment on his health or any details of his disappearance. Teng disappeared after leaving his home to meet with friends. Reportedly, policemen from the Beijing Public Security Bureau’s National Security Unit searched Teng’s home the following day, confiscating two computers, a printer, articles, books, DVDs, and photos of Chen Guangcheng.

- Wen Tao (文涛), former journalist and assistant to artist-activist Ai Weiwei, was reportedly released by June 27, 2011, though he was initially out of contact following this release. Originally missing since April 3, Wen was seized by plainclothes police officers outside of his girlfriend’s home in Beijing’s Chaoyang District. Wen was fired from his job at the Global Times’ English-language edition for reporting on a demonstration led by artists down Chang’an Avenue in February 2010 protesting the forced demolition of a Beijing arts district.

- Xu Zhiyong (许志永), a Beijing-based professor, legal advocate, and director of the Open Constitution Initiative (Gongmeng), which was forced to shut down in 2009, disappeared for one day on several occasions–around May 7 and again on May 20 and June 22, 2011. He was under police surveillance, or “soft detention,” from mid-February.

- Yuan Xinting (袁新亭), Guangzhou-based editor and activist originally from Sichuan Province, disappeared in early March of 2011 and was released from police custody and sent back to Sichuan sometime in July.

- Zeng Renguang (曾仁广, aka ‘Romantic Poet’ [浪漫诗人]), a Beijing-based human rights activist, was missing between February 22 and late March of 2011.

- Zhang Haibo (张海波), a netizen based in Shanghai, went to the location for the planned jasmine protest in Shanghai on February 20, 2011, and was taken away by the police. (As of early 2013, CHRD had not received further information about Zhang’s situation or whereabouts.)

- Zhang Jinsong (张劲松), driver of artist-activist Ai Weiwei, went missing on April 10, 2011. He was released on June 23, the same day Ai was released.

- Zhou Li (周莉), a Beijing-based activist, was missing for about a month from March 27, 2011. In 2010, Zhou was convicted of “creating a disturbance” and sentenced to one year in prison after participating in 2009 protests against Sun Dongdong (孙东东), the Beijing University professor who created an uproar in the activist community when he claimed that “99% of petitioners suffer from mental illness.”

- Zou Guilan (邹桂兰), a petitioner from Wuhan City, Hubei Province, was taken away from her home by national security officials on April 17, 2011. Zou returned home less than a month later.