“I don’t have control over my own body”

Comments Off on “I don’t have control over my own body”“I don’t have control over my own body”

Abuses continue in China’s Family Planning Policy

December 21, 2010

“I don’t have control over my own body. If I don’t have [the intrauterine device] inserted, I’ll be detained,” wrote a woman on an internet forum for mothers.[1]

“I discovered that in China, in this society, women in the villages have no human rights. Local family planning officials even said that I am under their management, that I do not have a choice, that whatever they say I have to do,” wrote another woman on the same forum.[2]

The year 2010 marked the 30th anniversary of China’s family planning policy. In recent years, the government has introduced many exceptions to the “one-child” aspect of the policy, leading to widespread speculation about its status and its future: Are people still bound by the policy, or can they pay their way out of it and have as many children as they want? Will the government relax the policy and allow couples to have more than one child?

CHRD argues that this focus is misplaced. Though the enactment of the National Population and Family Planning Law in 2002 was ostensibly aimed at reining in abusive practices associated with the family planning policy, coercion and violence continue to be used in its implementation.[3]Regardless of the number of children each couple is allowed to have, family planning policy continues to violate citizens’ reproductive rights, and will continue to do so until the current form of the policy is abolished.

In this report, CHRD documents serious violations of human rights associated with the implementation of the policy during the period 2005-2010. The report shows:

- Married couples are pressured to sign “contracts” with the government in which they promise to comply with various aspects of the policy;

- Advance permission is required before a woman can have a child;

- Married women are pressured to undergo regular gynecological tests to monitor their reproductive status;

- When a married woman reaches her birth quota[4] she is pressured to have an IUD inserted or be sterilized, thus denying her a choice of birth control method;

- If a woman becomes pregnant out-of-quota, including premarital pregnancy, she is often forced to abort the fetus, even if the pregnancy is advanced;

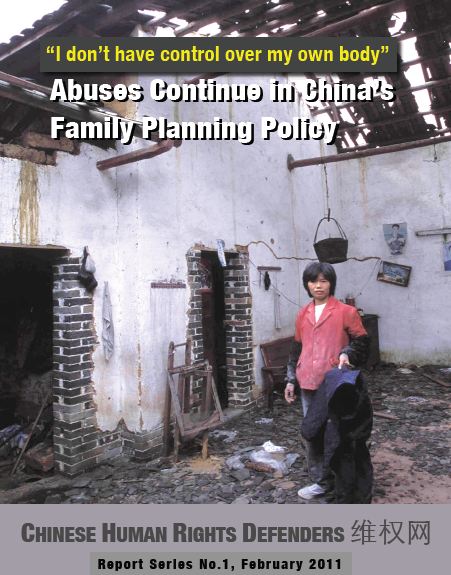

- As well as couples who have violated the policy, families and relatives have been punished with arbitrary detention, beatings, fines, and confiscation of property; others have been fired from their jobs and their out-of-quota children denied registration of the family’s household registration (hukou) booklet;

- As a result of the policy, parents and children face discrimination, as education, employment opportunities, and social services are linked to compliance with the policy;

- The arbitrary and inconsistent implementation of the policy across the country also results in unequal treatment of couples whose circumstances are otherwise similar.

The abuses listed above frequently occur during campaigns launched by local authorities to crack down on non-compliance with the policy, and at other times at the whim of the officials involved in implementing the policy. As well as being given incentives to do so, grassroots family planning officials are pressured by their superiors to fulfill certain targets in the implementation of family planning policy. Individual officers and their teams compete against each other to meet these targets, and those who deliver a certain number of the “four surgeries” (insertion of IUDs, sterilizations, abortions and late-term abortions) or the “three examinations” (examinations for pregnancies, the status of IUDs, and for gynecological diseases or illnesses) receive better pay, bonuses and promotions. Those who do not meet designated quotas face criticism and put their careers at risk. The women and men at the receiving end of the policy are seen as statistics, rather than individuals whose birth planning choices should be respected.

The implementation of the policy is extremely uneven. Not only do provincial governments adopt different regulations, but the work of implementation is subject to various local policy directives, as well as being open to interpretation by local officials. In some areas a woman pregnant with a second child after having a son might be forced to abort the fetus, while a similarly situated woman in another area might be asked to pay a fine. Furthermore, the motivation of local officials can play a significant role in how family planning policy is enforced. For example, in developed areas where population pressures have eased some officials may refrain from pursuing aggressive measures, while officials in other areas may order strict and brutal campaigns as a means to further their careers.

While it is not difficult for the rich and well-connected to circumvent the regulations, and for China’s growing middle class to buy their way out of the policy, many cannot afford to pay the fines levied—called “social maintenance fees”[5]—when they are in contravention of the policy. These fines have become an important source of income for local governments and family planning offices, particularly in rural areas. As local officials have wide latitude in setting the fines, the amount charged can be highly arbitrary.

Factors such as victims’ fears, poor legal knowledge, lack of confidence in the judiciary and the government, and the silencing of journalists and lawyers by government officials, have made it difficult for CHRD to obtain a detailed, nationwide picture of the implementation of the family planning policy. For example, we do not know with any certainty the total number of abuses, or how they vary across the country. Despite these limitations, based on the recent cases documented in this report it is clear that the problems are ongoing and directed mostly against women.

CHRD concludes its report by calling on the Chinese government to replace its abusive family planning policy with one based on choice and high quality reproductive health care, and for officials who have violated the rights of citizens while enforcing the policy to be held accountable.

We also call on the UN’s Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women as well as the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights to focus on the family planning policy in their next reviews of the Chinese government’s compliance with its obligations under the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, respectively.

The two committees should recommend that the government abolish the current policy in order to fulfill its international human rights law obligations. Moreover, CHRD urges the Chinese government to extend an invitation to the UN Special Rapporteur on Violence against Women to visit China.

Please click here to download the entire report in .pdf format.

[1]“Response from respondent 42: urgent!!! Can I refuse to have an IUD inserted? How do you handle the family planning officials and not have an IUD inserted?” (24楼 回复:急!!!不上环可以吗?怎么可以应付计生办不用上环?), March 26, 2008, http://bbs.ci123.com/post/2819169.html/15

[2] “Response from respondent 25: urgent!!! Can I refuse to have an IUD inserted? How do you handle the family planning officials and not have an IUD inserted?” (24楼 回复:急!!!不上环可以吗?怎么可以应付计生办不用上环?), March 26, 2008, http://bbs.ci123.com/post/2819169.html/15

[3] In China, the policy is officially referred to as the “family planning policy” (计划生育政策), also known as the “one-child policy.” In this report, the policy will be referred to as the “family planning policy” because some couples are allowed more than one child. Furthermore, it is the coercion and violation of reproductive rights, not the number of children allowed, that is the focus of the report.

[4] “Birth quota” refers to the number of children a couple is allowed to have. Most couples are only allowed one child, but some may have more than one child if they meet certain criteria set by the government. See Evolution of Family Planning in China, page 4.

[5] Shehui fuyang fei (社会抚养费)